The following story about William Jackson, a whaler from Spittal, first appeared in the Berwick Advertiser on 26th June 1896.

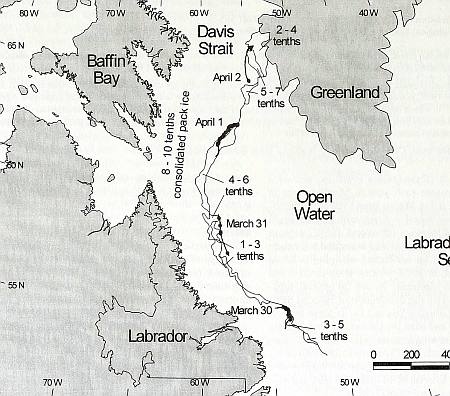

The story is based on William Jackson’s experience on the 19th century Berwick whaling ship Norfolk. The report gives a fascinating insight into the perils of hunting for whales during that period in the Davis Strait, situated between Baffin Island (Canada) and Greenland.

A narwhal tusk, which was brought back by a crew member of the Norfolk, is now held in Berwick Museum (natural history).

The last of the Berwick Whalers

We present to our readers the portrait of William Jackson, Spittal, the last survivor of the Berwick Whaling industry. Born in the year before the battle of Waterloo, he is now in his 82nd year. After a year or two in fishing boats, in 1832 he was bound to the late John Miller Dickson Esq., as apprentice on board the Berwick Whaler “Norfolk”, G. Harrison, master, at this time the sole representative of the Berwick Whalers, the Lively having been lost in the Davis Straits, in 1830.

The Norfolk was very successful in 1832-3-4, returning to port with 28, 32 and 30 fish, respectively in these years. The year 1835 was the most unproductive, as only three fish were killed. Worse was to follow, however, for in 1836, after having only killed two fish, she was frozen in the Davis Straits and was compelled to winter there. She had four companions in misfortune, the Thomas and the Advice of Dundee, the Greenwell Bay of Newcastle, and the Doe of Aberdeen. Each of these carried the same crew as the Norfolk, namely 50 men. On the 8th October they found themselves frozen in beyond hope of extrication until the following spring, and on the 13th December, the Thomas nipped her keel, and was hove up on the ice. This disaster caused the loss of two hands, and the 48 survivors of the crew were equally distributed amongst the other ships.

In February 1837, scurvy broke out amongst the crews, and many succumbed owing to the want of anti-scorbutics. After a long and tedious winter of five months, the Norfolk was the first to get clear of the ice and was again able to get under sail on the 16th March. Meanwhile friends at home had prevailed on the Government to send out three rescue ships. On the 28th March the Norfolk, while still in Davis Straits, sighted the Gambier, one of those rescue ships.

This map shows the Davis Strait between Baffin Island (Canada) and Greenland. Map by Internet Archive Book Images [no restrictions], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Norfolk’s companions in misfortune had even a worse fate. The Advice was picked up off the coast of Ireland, with only 8 or 9 of her crew alive. The Doe lost 32 men before getting clear of the ice, and the Greenwell Bay returned to port with the loss of 20 hands. Altogether, including those who had died on their passage home, of the 250 men forming the crews of the five ships 140 perished.

It is satisfactory to know that this loss of life was not altogether in vain, for it induced Parliament to take up the question, and compel foreign going ships to carry lime juice and other anti-scorbutics. Letters posted at Stromness had conveyed to Berwick the news of the safety of the Norfolk, but when she came into Berwick Bay on the morning of May 5, 1837, joy bells rang from the Townhall spire, and the children of Spittal got a holiday. This was her last voyage as a whaler, as she was sold to a Hull firm in 1838, and became a total wreck off Memel a year or two afterwards.

Jackson continued to follow his vocation as a sailor in various parts of the world, and latterly in the coasting trade, until over 60 years of age. Of an upright and consistent life and character, he is a well known figure in our town, where he has many friends, who most deservedly hold in high esteem the last of the Berwick Whalers.

Our portrait is from a photograph by Mr. Green, Berwick.

An ice-covered fjord on Baffin Island, with the Davis Strait in the background. Photo: NASA – Earth Observatory.

For a history of whaling, written by Gordon Jackson, See this article in Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Banner picture: Humpback whale and sailing ship in the Davis Strait (1870), by Jens Erik Carl Rasmussen 1841-1893 (via Wikimedia Commons).