The story of the building and opening of the Tweed Dock first appeared in the official centenary brochure in 1976. Written by the well-known and respected local historian Francis M. Cowe, the original text is reproduced below with kind permission.

The building of the Tweed Dock

In the second half of the eighteenth century the Port of Berwick enjoyed a boom such as it had not known since the middle ages. The Berwick smack, a type of sailing vessel built locally primarily to carry salmon speedily to London, captured a great amount of trade in other commodities, notably grain and eggs, which were brought overland from considerable distances for transmission to the Thames.

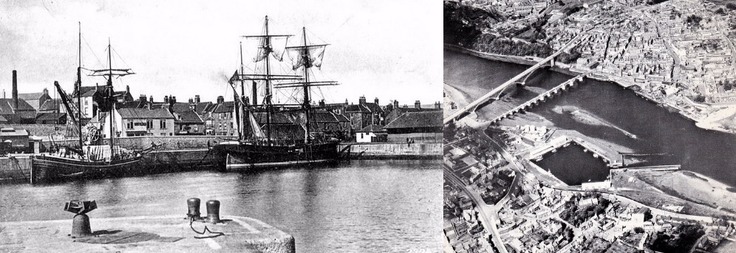

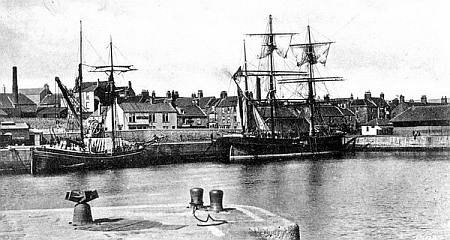

Two sailing ships moored at the Carr Rock, Spittal, in the early 20th century.

© Berwick Record Office, BRO 426-7-7-25-SL-111.

The smacks also carried passengers more quickly and cheaply than any other form of transport. They sailed from the old quay below the bridge, which was still the only part of the harbour with facilities for loading and unloading. By about 1800 much of this trade had been lost to Leith, and it may have been the spur of competition that caused the merchants of the town to promote an Act of Parliament for rebuilding the pier and improving the harbour. This act, passed in 1808, established the Harbour Commissioners in office, and they completed the new pier, extended the quay and built the stone jetty at the Carr Rock. Despite these measures trade scarcely improved.

The harbour was still highly unsuitable for the larger steamships that had begun gradually to replace sailing vessels, and in the middle of the nineteenth century the railway took away most of the coastal trade almost overnight. However, larger ships were attracted to the port, particularly by the needs of new industries established in Tweedmouth and Spittal, and it was evident that improvements would need to be made for their accommodation. A second Harbour Act was passed in 1862, which contained provisions for the election of fifteen Harbour Commissioners, and ten years later another Act of Parliament empowered them to make a wet dock on the shore of Tweedmouth between Berwick Bridge and St Bartholomew’s Church, and an embankment from the west end of Berwick Bridge to the landward end of the Carr Rock pier.

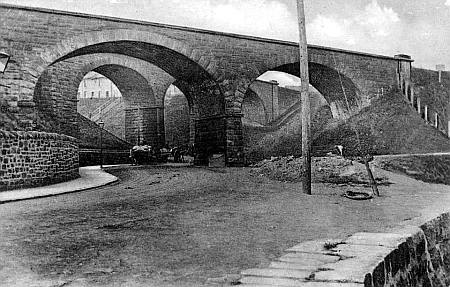

The twin railway viaducts first used in 1878, were situated at the Spittal end of the Dock Road. Only one now remains. © Berwick Record Office.

On the embankment they were to build the road which became Spittal low road. They also had powers to construct coal staithes and to enter into an agreement with a railway company for the construction of a railway line to the new dock. Consideration had at first been given to the construction of a dock at the ballast quay on the north side of the river, but it was clear that there was both a greater demand and a better site for the proposed dock on the south bank. It would replace a large mud bank which was exposed at low tide, and it would be much easier of access than any similar structure on the northern shore. The plans of the Dock were drawn up by the famous engineering firm, D. & T. Stevenson of Edinburgh (David and Thomas Stevenson were respectively uncle and father of Robert Louis Stevenson).

The contractors who executed the work were Messrs. A. Morrison & Son, also of Edinburgh. Work began in 1873 with the building of a coffer dam within which the dock walls were constructed. They were made of concrete, and the upper portions were faced and capped with granite. The floor of the Dock was puddled with blue clay to make it watertight. In plan the Dock is a five-sided figure, with 1,550 feet of quay.

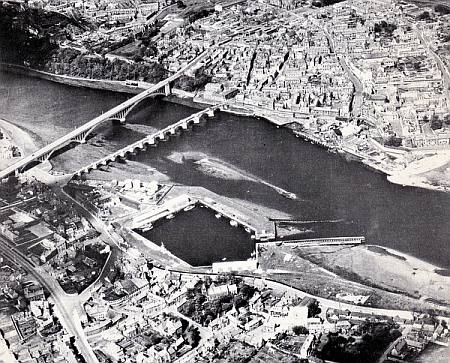

The embankment and railway line to the Tweed Dock can be clearly seen on the right of this 1950s photograph. © Eric Binnie.

It encloses three-and-a-half acres, and the depth of water at ordinary spring tides is twenty-one feet. The entrance to the Dock is forty feet wide, and the sill of the gates reduces the depth of water by two feet. Entrance to the Dock by large vessels today is only possible for about an hour either side of high water. Inside the Dock, in the north-west corner, there is a slipway for timber which is one of the original features. A steam crane was provided for loading and unloading. Outside, a channel was dug from the Dock gates to the main stream of the river, and its course is marked by a wooden quay or jetty. The total cost of the works exceeded £40,000.

The Dock and its ancillary works greatly improved the south bank of the river, and its access roads also made for much easier communication between Tweedmouth and Spittal. The Dock railway line leading to Tweedmouth Station was opened on 16th October, 1878, by the North Eastern Railway Company. Its steep inclines were suited only to very small trains and it was eventually closed in the 1950s. The embankment by the river and one of the railway’s two bridges were demolished in 1975.

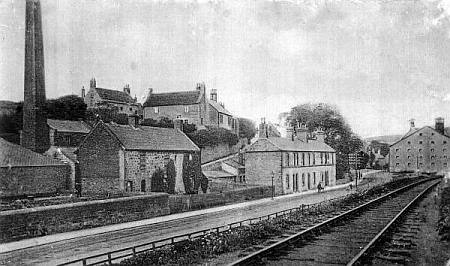

This early 20th century photograph shows the railway line approaching the Tweed Dock from the Spittal viaduct, with the former Tweedmouth Maltings, which burned down in 1933, pictured furthest right in the background. The Tweedmouth Maltings were owned by Messrs. J. P. Simpson & Company. The Dock Road can be seen clearly on the left. © Berwick Record Office.

The opening of the Tweed Dock

The official opening of the Tweed Dock was fixed for Wednesday, 4th October, 1876. In fact, it had already had an unofficial opening, witnessed by a large crowd of people, some six weeks earlier when the berths at the Carr Rock were overcrowded and more space was needed for new arrivals.

It was in the middle of August that the master of a three-masted schooner from the West Indies refused to enter the harbour until suitable accommodation was made ready for his vessel. The channel to the new Dock was quickly dredged and four ships were allowed in on the afternoon of Saturday, 19th August. The ship that had the honour of being the first to enter the Tweed Dock was the brig “Acacia” of Hartlepool, and she was followed by the brig “Para” of London, the schooner “William” and the brig “Vesta.” The three-masted schooner was berthed at the Carr Rock. When the four ships had discharged their cargoes and departed the Dock seems to have been unused again until the day of the official opening.

On this occasion the Mayor of Berwick, Andrew Thompson, proclaimed an official half-holiday in the town, and the ceremony began with the ringing of the bells in the Town Hall. The rest of the story is best told from the local papers:

The Mayor and Town Council assembled at the Town Hall at half-past one o’clock, from which place they marched, preceded by the Sergeants-at-Mace, to the Harbour Office on the Quay. Here they were joined by the Harbour Commissioners, and a large number of the principal inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood.

At two o’clock the company embarked on board the steam-tug Tweed and sailed down the river as far as Spittal. The tug was then turned, and sailed down to the dock, which was entered about half-past two o’clock. As the tug entered the dock cheers were raised by a large concourse of people who had assembled to witness the proceedings. At the south side of the dock the company landed and marched in procession round the dock, and halting at the dock gate, witnessed the entrance of H.M. Gunboat Tyrian, which is to be accommodated in the dock during the winter.

Afterwards the brig Vedra of Sunderland was towed in by the steam-tug Tweed….

The formal opening speech was made by the Recorder of Berwick, William Thomas Greenhow, and the company then partook of wine and cake at the blacksmith’s shop before marching back over the bridge to the harbour office.

An early 20th century photograph showing two sailing ships in the Tweed Dock. © Berwick Record Office, BRO 426-687.

The occasion appears to have been successful and enjoyable, though one bystander wrote to the local Press anonymously, complaining at the funereal nature of the proceedings.

It is certain that the evening’s celebrations were enjoyed, when 110 gentlemen attended a special dinner in the King’s Arms Assembly Rooms, and downed an enormous meal and gallons of wine. A great many speeches were made, all of them optimistic in character. The speakers included the Mayor, the Recorder, C. L. Gilchrist, Chairman of the Harbour Commissioners, Capt. David Milne Home, one of Berwick’s two Members of Parliament, representatives of the Army, the Navy, the Coast Guard, the North Eastern Railway Company, and of the engineers and contractors. It was agreed that the Dock was a valuable addition to the Harbour which was long overdue, and there was a confident forecast that a second wet dock would be needed within a year or two, a prediction that has not been fulfilled.

It was the general opinion that the main trade in the Dock would be in the shipment of coal, and some of the first ships to use the Dock were colliers. The Harbour Master at the time of the opening was Captain Robert Ferguson, who had been appointed in 1867 and who was closely involved with the building of the Dock.

Main text © Francis M. Cowe

This photograph shows what is believed to be the former convict ship ‘Success,’ moored in the Tweed Dock. She toured the world on exhibition between the years of 1895-1942. Launched in 1840, made of teakwood and measuring 117 feet 3 inches x 26 feet 8 inches x 22 feet 5 inches. In her first fifty years of service she had a variety of roles including emigrant ship, trader and prison hulk. She was destroyed by fire on the 4th July, 1946. © Berwick Record Office, BRO 426-7-2-008.