The 19th century social reformer James Redpath was born in Berwick-upon-Tweed in 1833. He became a pivotal figure in many of the important improvements in nineteenth-century American political and cultural life, arguing for abolition of slavery, civil rights and Irish nationalism, among other things. His fascinating story begins with the Redpath’s family history in Berwick, in the early 19th century.

Ninian Redpath, the father of James, was born in 1806 in the Scottish Borders; his brother John worked in agriculture, and his other brother James was a shopkeeper in Berwick. Ninian received a good early education, possibly at a private school in Tweedmouth run by a relative called James Davidson, and this gave him the start in life which (according to an 1822 directory for Northumberland) then enabled him to run his own Academy in Union Street in Berwick, now Ravensdowne.

Private schools were the order of the day in 19th century Berwick. Children of the wealthy would receive their education from the endowed grammar school, the poor being given an education of sorts from the various charity schools. And for those families with middle income, it was a case of paying varying amounts at the various academies in the town for their children to receive a better education than that afforded to the poor.

By 1833 Ninian was teaching from premises which he owned in 79 Church Street, and where he ran his own day school. Ninian’s premises in Church Street appears not to have the property value for him to qualify as a Freeman of Berwick, as he is not listed as eligible to vote in the parliamentary elections before the Reform Act, 1832.

Ninian married Maria Main, who was born in England, on 13th November 1832 at Holy Trinity parish church in Berwick (though both of them were members of the United “Seceder” Presbyterian Church in Golden Square). In 1834, Maria was running her own business as a dressmaker at the family home in Church Street.

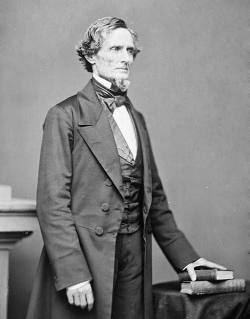

Portrait of James Redpath (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

James Redpath was born in Berwick on 24th August 1833, and baptised the following month in the Golden Square Church on 22nd September. He was reportedly the oldest of seven children; the others known to have survived into adulthood were Jane (b. December 1837) Mary (b. December 1840) and John (b. December 1844). James was small of stature, and in adulthood he measured only 5 feet 4 inches and weighed around 7½ stone. In 1839 Ninian Redpath became the schoolmaster at the newly opened Spittal School (supported by the British and Foreign School Society), and his family moved with him to live in Spittal. The young James Redpath grew up there and received his education at his father’s school where he developed an interest in English literature.

After completing all his exams successfully at thirteen, James left Spittal School. He resisted his father’s wish that he should be become a clergyman and he instead served an apprenticeship in the printing trade. He also learned shorthand reporting, and wrote articles for the local press.

In 1848 Ninian and the young James together published a new edition of the Border History of England and Scotland (1776), by their relative George Ridpath (Ridpath being a variant spelling of Redpath). Ninian and James composed the type for the book which was printed by Catherine Richardson publisher of the Berwick Advertiser. George Ridpath had been a minister at Stitchhill, Kelso, in the Scottish borders from 1743 to 1772.

Emigration

Near the end of the 1840s, the Redpath family were experiencing financial difficulties, as competition from the new publicly funded schools reduced the intake of pupils at Spittal School. Ninian considered emigration to America, to join his brothers James and John who had already settled there. In 1850, Ninian arrived with his family in Allegan County, Michigan, where he bought land and took up farming. James was 17 years old.

James Redpath in USA

| In America James Redpath soon abandoned farming and went to New York, where he joined the staff of the New York Tribune. The following summary of his career appeared in a newspaper when he died in 1891: | In the course of his career as a journalist, social campaigner, and entertainment impresario, James Redpath became acquainted with some of the most prominent and influential figures in the United States: |

| “In 1854 [James Redpath] started to walk through the Southern States. While at Augusta, Georgia a yellow-fever epidemic broke out, and he volunteered as a nurse, and remained there six weeks until the plague and its panic had subsided. From Augusta he went to New Orleans, thence to St. Louis, whence he was sent to Kansas to report the “border war” for the St Louis Democrat. His reputation from his letters then became national.

“From Kansas he went Hayti [Haiti] in search of health. When he returned, the officials made their Emigration Commissioner. He negotiated with President Lincoln for the recognition of the Republic of Hayti, and sent nineteen colonies of coloured people from here to Hayti.

“During the civil war he was correspondent at the front for the New York Tribune and Boston Journal. After the war was over he stayed in Charleston, and was Superintendent of Education under the Freedman’s Bureau for the department including South Carolina, Georga, and Florida.

“He next went to Boston, where he organised the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, which for several years controlled the system of public lecturing for the whole country.

In 1877 he started a newspaper syndicate in Washington, which was not a success, and then came to New York, where he resumed active work as a newspaper man, and was sent by the Tribune as special correspondent to Ireland during the famine of 1879-’80. His graphic descriptions of the sad scenes of misery and starvation which he witnessed in that unfortunate country (which were reproduced in the Irish American at the time) was the first authentic account by an American visitor that the masses of people in the United States had that another famine had overtaken the sorely tried peasantry of Ireland. He returned to New York in 1880, having, as he described himself, been thoroughly converted by what he had seen in Ireland that he regarded himself thenceforward as a naturalised Irishman: and to the last day of his life he acted in accordance with this principle.

“After a lapse of a year he revisited Ireland, and was greeted with unbounded enthusiasm by the people of Dublin and all of the principal towns in the West, Southwest and Northwest, where the distress was greatest, and where the people, grateful for the overflowing sympathy which America had shown them in the hour of their distress, passed votes of thanks to him for being one of the first to stir up the fount of charity. He made many speeches in support of the Land League, at the time, and so identified himself with the National movement, that the late W. E. Forester, who was then Chief Secretary for Ireland, had a warrant issued for his arrest, which, however was not executed.

“On his return to New York he published Redpath’s Weekly, which lived for two years. He was next appointed managing editor of the North American Review, by Allen Thorndyke Rice. It was while working on the Review that he received the stroke of paralysis which indirectly led to his death. By advice of his physicians he made another voyage to Ireland, and after a stay of a couple of months, returned so much benefitted in health that he took the same place on Belford’s Magazine that he held on the Review, and retained it until just before the accident, when he joined forces with Mark Twain.

“Perhaps the strangest purely literary work he did was in helping prepare the memoirs of Jefferson Davis the Confederate leader. He went to the family home ‘Beauvoir’ in Biloxi, Mississippi, and remained there some time, collating and selecting the proper material from Mr. Davis’s private papers. It was one of the peculiar echoes of the war time that this original Abolitionist learned to look on Mr Davis in a new light at Beauvoir, and to openly admit the honesty and justice of many of the ex-Confederate’s principles, and thus remould the entire character of his views of the great anti-slavery contest.

“When Mr. Redpath was stricken with paralysis it was a woman who nursed him back to life and health. She was Mrs. Carrie Chorpenning, of Washington, whom he had long known. A few months after his recovery, in September, 1888. Mr. Redpath and Mrs Chorpenning, were married.

“Mr. Redpath was the author of several books, notably “The Roving Editor; a Handbook of Kansas Territory;” “The Public Life of Captain John Brown,” “Echoes of Harper’s Ferry,” and “A Guide to Hayti.” He was an intensely earnest truthful man, gifted with a bright and genial manner that won and kept him many friends. The Irish people at home and here, in particular, can never forget the faithful services he rendered in their behalf. – – From Irish-American Weekly, 21 February 1891.

James Redpath died in New York on 10th February 1891, after an accident in which he was struck by a horse-drawn trolley car. His body was cremated on Long Island. Redpath was married twice. He left no children.

|

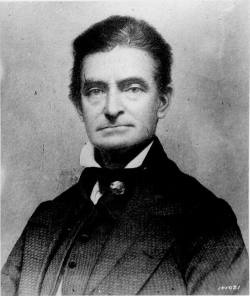

Abolitionist John Brown, c.1856 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) In 1855, James Redpath moved to Kansas Territory, reporting on slavery for several newspapers in the north. There he joined the controversial abolitionist John Brown in his campaign to make Kansas a Free State. In 1858 Brown encouraged Redpath to move to Boston to help rally support for his plan for a slave insurrection in the South. After the failure of Brown’s 1859 attack on Harpers Ferry, Virginia, Redpath wrote a sympathetic biography of the executed abolitionist, The Public Life of Captain John Brown (1860).

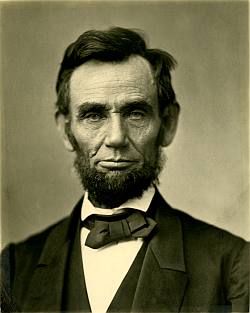

Abraham Lincoln, on 8 November 1863. Photo: Alexander Gardner (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons. James Redpath became acquainted with Abraham Lincoln and advised him on the independence of Haiti. Redpath had visited Haiti in 1860 and was appointed by the Haitian president Fabre Geffrard as his representative to lobby for diplomatic recognition of the country. Redpath founded the Haitian Emigrant Bureau in Boston and New York, and in 1861 he published The Pine and Palm, a newspaper which sought to encourage skilled black workers to emigrate to Haiti. In 1863 Abraham Lincoln officially recognised Haiti, along with Liberia, as being independent and sovereign countries.

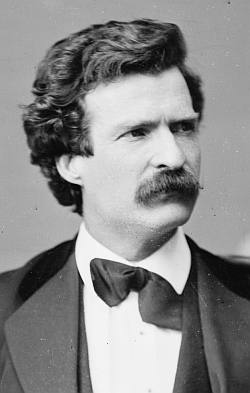

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (1835-1910), better known as Mark Twain. Photo: Mathew Brady (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons. In 1868 James Redpath, set up the Boston Lyceum Bureau (afterwards the Redpath Lyceum Bureau), an agency which promoted lectures by leading American authors and public figures. Among its first clients was Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens), who made two extensive lecture tours in 1869/70 and 1871/72. Later, musicians and dramatic performers were also managed by the agency. When Mark Twain was no longer touring, he remained a friend of James Redpath. While at work on his autobiography in 1885, Twain was assisted by Redpath, who took dictation. To view letters between James Redpath and Samuel Langhorne Clemens, held by the Mark Twain Project: – Click here for Twain’s incoming letters from Redpath – Click here for Twain’s outgoing letters to Redpath.

Jefferson Finis Davis (1808-1889). President of the Confederate State of America. Photo: Mathew Brady (public domain), via Wikimedia Commons. The reasons why the abolitionist Redpath helped to complete the memoirs of the Confederate President Jefferson Davis were later explained in a magazine article. Redpath said that he had never met a man with more “intellectual integrity” and “refined and benignant character” than Davis. While neither had changed his essential creed, each respected the other’s convictions. Both sides in the war had fought honourably for what they believed, but “now that the war both of bullets and of ideas is over . . . it is time to drop, and drop forever, the old war-cant about Rebellion and Treason.”

|

Redpath on slavery

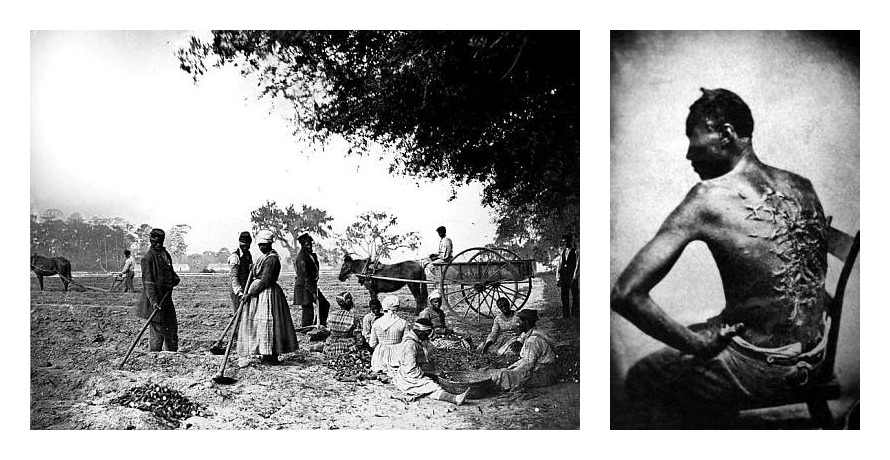

Throughout his career as a journalist, Redpath sought to advance the cause of black people, initially by interviewing slaves and publishing their testimony about conditions of life, and subsequently by more radical support for black emancipation.

Left: James Hopkinson’s plantation slaves, planting sweet potatoes (circa 1862/63). African American men and women hoe and plough the earth, while others cut piles of sweet potatoes for planting. One man sits in a horse-drawn cart.

Photo: Henry P. Moore (Library of Congress image), via Wikimedia Commons.

Right: Scars of a whipped Mississippi slave, photo taken April 2, 1863, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA. Original caption: “Overseer Artayou Carrier whipped me. I was two months in bed sore from the whipping. My master come after I was whipped; he discharged the overseer. The very words of poor Peter, taken as he sat for his picture.”

Photo: McPherson & Oliver (National Archives and Records Administration), via Wikimedia Commons.

Redpath in Ireland

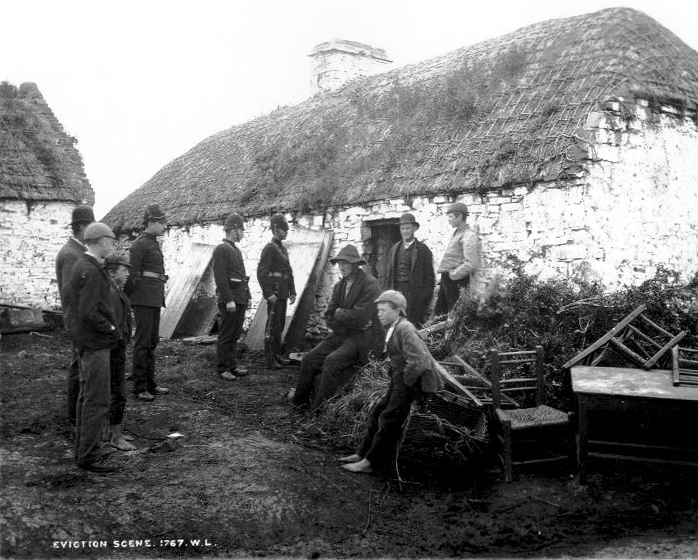

In the 1880s, Redpath toured Ireland to report on the famine and the land tenure system, and he became deeply affected by the conditions which he saw there. Thereafter he became an ardent supporter of Irish nationalism.

Another useful account of Redpath’s life can be found in the article by Patrick Maumé, “James Redpath”, in the Dictionary of Irish Biography. It explores in some detail his various visits to Ireland and his growing involvement with the Irish nationalist movement.

An Irish family evicted at Moyasta, County Clare, during the Land War (circa 1879). James Redpath was in Ireland shortly after this to report on conditions for the New York Tribune. Photo: from National Library of Ireland, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sources:

John McKivigan. Forgotten Firebrand: James Redpath and the making of nineteenth-century America. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2008.

James M. McPherson. The Abolitionist Legacy. Princeton University Press, 1975.

“James Redpath”, in American National Biography, vol.18, pp. 257-258. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Marriage Registers of Holy Trinity Church, Berwick-upon-Tweed (Berwick Record Office)

Baptismal Register of the United Associate Congregation, Golden Square, Berwick-upon-Tweed. (Berwick Record Office).