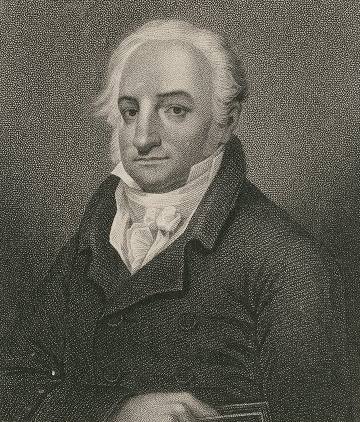

An engraving of George Frederick Cooke, made by Robert Cooper; published 1813. [Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons].

George Frederick Cooke (1756?-1812), who became one of the most famous actors of the late 18th/early 19th centuries, had associations with Berwick in his early life, though the details are often sketchy. By some accounts he was born in the town, but the likelihood is that he was born in Westminster – or in Dublin – as the son, possibly illegitimate, of a military man. At any rate in his childhood, probably in the early 1760s after his father’s death, he came with his mother to live in Berwick, and was sent to school there. When his mother died around 1764, he was looked after by his two aunts who also lived there, and they enabled him to continue his schooling. In about 1766 or 1767, while he was still at school, Cooke saw his first play acted on stage. Some members of the theatre company in Edinburgh came to Berwick to perform in the Town Hall, where they gave The Provok’d Husband, or A Journey to London (the popular comedy by the dramatist and architect John Vanbrugh). Cooke’s imagination was captured.

On leaving school Cooke was apprenticed to a Berwick printer, John Taylor. (This John Taylor was probably the second son of Robert Taylor, the Berwick and London printer who was sued for breach of copyright in a landmark case concerning an edition of James Thomson’s The Seasons. John Taylor conducted his printing business in Marygate and in London.) Another visit to Berwick by Edinburgh actors in April 1769, again performing in a makeshift theatre in the Town Hall, confirmed Cooke in his dramatic interests, and he and some other local boys are said to have formed their own company and used a deserted barn to rehearse a performance of Hamlet.

Another Scottish acting company visited Berwick in 1770, and later that year the townsmen put on their own performance of Cato (presumably the tragedy by Joseph Addison) in which Cooke (who was then 14) played the role of Lucia.

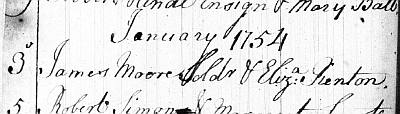

The exact facts of Cooke’s birth are vague. He himself said that his mother’s name was Renton, and she was the daughter of the laird of Renton, near Lamberton. The marriage registers of Holy Trinity Church in Berwick record a marriage of Elizabeth Renton with James Moore, a soldier, on 3rd January 1754, as shown in this extract. Was this Cooke’s mother? The dates make it a possibility. There could be various explanations for the discrepancy of the name of Cooke rather than Moore: after he was orphaned, he may have taken the married surname of one of his guardians; or his mother may have been deserted by her husband and then become the common law wife of another soldier called Cooke. Given that one account of his life declared Cooke to have been illegitimate, the chosen name could represent a bid for respectability. The truth however must remain a matter of speculation. (Image taken from the Parish Registers (Baptism, Marriage, Burial 1695-1794), by kind permission of the church of Holy Trinity and St Mary, Berwick-upon-Tweed.)

By June 1771 Cooke had been released from the indentures of his apprenticeship in printing and he made a trip to London, where he continued amateur acting, and also to Holland, “on business”. But he was soon back in Berwick and in the summer of 1773 the arrival of a strolling company of actors allowed him to see a range of plays in the standard repertoire: King Lear, Hamlet, Richard III, Venice Preserv’d, Romeo & Juliet.

Cooke went to London again in 1774 and his professional acting began soon after. For the next 27 years, he learned and practised his craft mainly in provincial theatres, gradually building himself a star reputation. He is said to have mastered over 300 roles, but he also acquired a reputation for unreliability and alcoholism. He made only two brief appearance at London theatres in this period, until in 1800 he was eventually invited to join the Covent Garden company. He made his debut there as Richard III, the role for which he became most famous, and many others followed.

One further appearance in Berwick is recorded, in the summer of 1807, when he followed engagements in Glasgow and Edinburgh with a visit to the town for six nights. On this occasion he would have appeared in Stephen Kemble’s theatre, by then erected behind the King’s Arms. He gave his last performance in Berwick on 17 August 1807.

Cooke was still performing regularly in London, but by 1810 his troubles there were escalating and his position became untenable. He accepted an invitation to appear in America, and sailed to New York. He spent the next year and a half giving 160 performances in various cities on the East Coast with enthusiastic receptions. However drinking and financial problems were worsening his health, and he died in New York from cirrhosis of the liver in September 1812.

An engraving by Richard Woodman, after Samuel Wilde (1808) showing Cooke in the role of Sir Archy MacSarcasm in Love à la mode, by Charles Macklin. [Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

Cooke’s reputation as an actor was always controversial but he is generally recognised as one of the leading figures between David Garrick (1717-1779) and Edmund Kean (1787-1833). In the words of one summary: “Arguably he was the first true British romantic actor, ranking in the annals of the stage with the small group of great actors of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. He was the first major foreign star on the American stage, and his appearance there marked the inception of the star system in the United States.” [ODNB]

One of his modern biographers describes his technique and character:

“Physically and vocally he lacked elegance. Of middle height, with shorter arms than normal, he moved angularly rather than gracefully. He was not handsome – all the portraits emphasise the too-prominent nose – but his features were under extremely flexible control, and his eyes could flash signals that even in the under-lit theatres of his day were unmistakable. His voice was harsh, limited in its tonal modulation, and easily subject to hoarseness. At the same time it was extremely powerful and flexible – again and again we find comments on his whisper that could penetrate right through the house. Power was its asset, lack of gentleness its limitation; he had no tones for the softer emotions, we are told.

“… A man of undoubted intelligence, he read widely, as his journals show, and thought deeply and critically about what he read. He could be kind, thoughtful, benevolent – whether the helping hand was given to the pregnant wife of a poor fellow-actor, to an old woman trudging along the road while he passed in a post-chaise, or to the benevolent fund of a theatre a hundred and twenty miles away.” [Arnold Hare. 1980]

A modern historian of the British theatre sees Cooke as in many ways the opposite of his contemporary and rival, John Philip Kemble, and characterises him as follows:

“A fascinating and brilliant actor with a penchant for strong drink and an overdeveloped sense of amour propre, he quarrelled frequently, married serially, and was imprisoned for debt. Square-jawed and hook-nosed, with a wide mouth and eyes set far apart, he may have looked like a pugilist,, but his performances could be electrifying.

“…at his best, Cooke displayed an original imagination and a commitment to hard work, which enabled one writer to say of his Hamlet, ‘the beauties are so many, that ill-nature and envy must stand up, and say to all the world, “This is an actor” ‘.

“[Drink] ruined Cooke’s life as well as his career. From early on there are reports of him failing to appear when he had been billed. One contemporary wrote, ‘When the tragedian was intoxicated, he was overbearing, noisy and insufferably egotistical…’

“…he had the rare ability to act with his partner on the stage: ‘he never loses sight of the character, or the situation of the other performers who are engaged in the scene with him’. He was totally involved even when not speaking and understood the importance both of the overarching conception of the part and the need for convincing detail in the playing. When sober, it was agreed, Cooke had no equal.” [Robert Leach. 2019.]

Sources:

Dunlap, William. Memoirs of the life of George Frederick Cooke. 2 vol. 1813.

Hare, Arnold. George Frederick Cooke: the actor and the man. The Society for Theatre Research, 1980.

Leach, Robert. An illustrated history of British theatre and performance. Vol.1. Abingdon: Routledge, 2019. pp.587-589.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. [online 3/1/2008; retrieved 26/11/2019]; article on “George Frederick Cooke“, by Don B. Wilmeth.

Banner images [public domain via Wikimedia Commons]:

(a) Cooke as Stukely, in Edward Moore’s tragedy The Gamester; engraving by John Rogers, published 1823.

(b) Cooke as Iago; mezzotint by James Ward after James Green, published 1801.

(c) Cooke as Richard III; painting by Thomas Sully (1811); (photo by Wmpearl [CCO] )