Belford, some 15 miles south of Berwick, just off the A1, lies at the junction of the coastal path with a route through the hills to the west. For early settlers, the Belford Burn provided fresh water, and the surrounding crags, security. There is limited evidence of prehistoric settlement in the vicinity. Probably Belford was on the route used by the Anglo-Saxon kings of Northumbria on the way from Bamburgh to their palace at Yeavering.

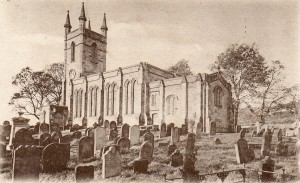

After the Norman Conquest there are clearer records. In 1174, the chronicler Jordan Fantosme, recorded that Belford was raided by mercenaries from Scotland, and that women fleeing to the church for safety, were captured. This church or chapel, which is thought to have been on the crags to the north of the village, was controlled by the prior and monks of Nostell Priory until the Dissolution of the Monasteries. At this time the Manor of Belford seems to have been centred to the west of the village, where West Hall Farm now is.

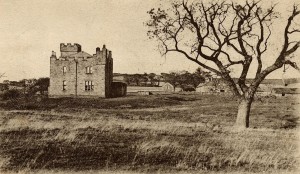

The appearance of the present Farm buildings dates from Victorian times, but archaeological excavations at that time found evidence of a mediaeval moated stronghold, and a pair of spurs, now sadly lost, were found in the moat. In 1272, the then Lord of the Manor, Walter de Huntercombe, was charged by the Crown with assisting pirates who had seized the goods of Spanish merchants and landed with them on Holy Island. In 1296, Parliament’s attempt to raise a tax to help pay for Edward I’s war with Scotland, assessed the wealth of Belford at £57. 19s. 4d – with tax due of £5. 5s. 4¾d.

Throughout the middle ages, Belford found itself on the front line of the border warfare between England and Scotland, and it is claimed that Well House is the only building in the village to have survived the harrying of the Scots.

By 1503, when Margaret Tudor travelled north to marry James IV of Scotland, things must have improved, as, after leaving Alnwick, she stopped in Belford to eat. Records show that, under Queen Elizabeth I, Belford became one of the network of Post Towns through which royal messages were sent across the country. Even so, it was hardly a centre of attraction. In 1639, a visitor described it as the most miserable beggarly sodden town, or town of sods, that ever was made in an afternoon of loam and sticks. In all the town not a loaf of bread, nor a quart of beer, nor a lock of hay, nor a peck of oats and little shelter for horse or man.

At some point in this period the church was moved to the centre of the village, but did not flourish during the unsettled times of the Civil war. There was a further rebuilding at the end of the seventeenth century, creating much of the parish church we see today.

Situated so close to the Scottish border, many of the workers who came to the village brought with them a different religious tradition, and by the middle of the eighteenth century, religious needs were also met by three different Presbyterian churches, one in West Street, one in Nursery Lane and one just outside at Warenford.

The man responsible for changing Belford’s fortunes was Abraham Dixon (1689-1746) of Newcastle, who bought the estate for £12,000 in 1726, as part of his strategy to raise the standing of his family from merchants to country landowners and gentlemen. In 1742, Dixon purchased a licence to hold a weekly market and two fairs annually at Belford, one at Whitsuntide and the other in August, so making Belford the centre of local commerce.

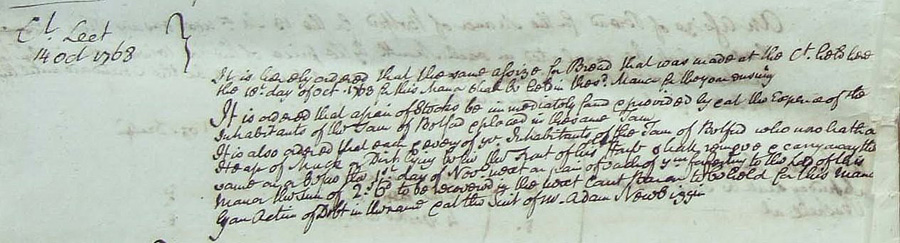

Dixon’s work was continued by his son, another Abraham, who also built himself a new and prestigious house, Belford Hall, on the eastern edge of the town. When Arthur Young visited Belford in 1770, he described the establishment of a woollen mill, a tannery, collieries and large lime kilns, with the result that the population had increased from 100 to 600 in the previous thirteen years. Dixon also improved the roads. In addition, he made use of the manorial court to enforce levels of hygiene, banning the grazing of swine in the streets and requiring the removal of muck heaps from outside the houses.

Extract from Belford Court Leet 1768 showing purchase of stocks and punishment for those leaving muck heaps in the street

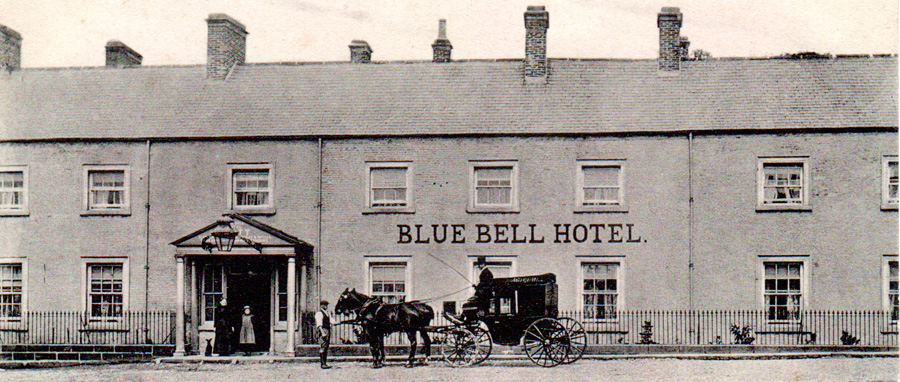

Belford’s status as a mail coach town, also added to its prestige, and resulted in the development of the Blue Bell Hotel as a notable coaching inn.The first half of the nineteenth century probably saw Belford at the peak of its prosperity – a flourishing market town, whose inhabitants were also employed in agriculture and coal mining in the bell pits on Belford Moor. In the 1820s, the Clark family, who succeeded the Dixons as squires, rebuilt the centre of the village with terraces of plain Georgian houses.

With the passage of the Poor Law Amendment Act in 1834, Belford became the centre of the newly established Belford Union, the organisation responsible for the care of the poor, the elderly and the infirm for the area from Ross in the north to Tughall in the south, and run by an elected Board of Guardians. The Workhouse to which those who could not look after themselves were sent, was built in West Street, where Bell View now stands. Very shortly afterwards, the Government recognised the advantages of having a group of people able to take charge of local problems. Soon the Board of Guardians found themselves responsible for roads, school attendance and vaccinations. In time these responsibilities resulted in Belford becoming the centre of the Rural District Council.

The arrival of the railway from Newcastle to Berwick in 1849, and the building of Belford Station outside the town, marked the beginning of a gradual decline in its fortunes.

Although Belford retained its Post Office status, largely thanks to the enterprise of the landlords of the Blue Bell who contracted to take and bring the mail from the railway station to the Post Office, there was now little reason for travellers to interrupt their journey at Belford, and, over time, the attractions and accessibility of larger markets at Berwick, Alnwick and Newcastle resulted in the decline of the weekly market and the fairs.

Belford remained an estate-owned town or village, largely unmodernised, until 1923, when the last squire, George Dixon Atkinson Clark died. His son, Henry, put the estate up for auction, and many of the residents were able to buy their own houses. Belford Hall, however fared less well – proving difficult to modernise or adapt to other uses, and after housing the army during the Second World War, it fell into ruin, only just being rescued and transformed into flats in the 1980s. The village itself saw little change until the 1940s. Then a new school was built at the west end of the village, and new housing to the south of West Street. The most significant change, however, came in 1983 when a new bypass took away the heavy traffic from the centre of the village.

Although the lack of modernisation at the beginning of the twentieth century meant that poor water supplies and sanitation were issues for residents until well into the century, it also preserved the shape and features of Belford as it was in its heyday, which gives it its unique charm. Today, the history of Belford and of its residents is recorded in displays in the recently opened Hidden History exhibition and in the gallery of the Parish Church.

Sources:

Bateson, Northumberland County History, Vol.1, 1893

J. M. Bowen, A Poor Little House…, 2005

Belford & District Local History Society, Aspects of Belford, 2008

Belford & District Local History Society, Further Aspects of Belford, 2011

Belford & District Local Histroy Society, Bygone Belford, 2010