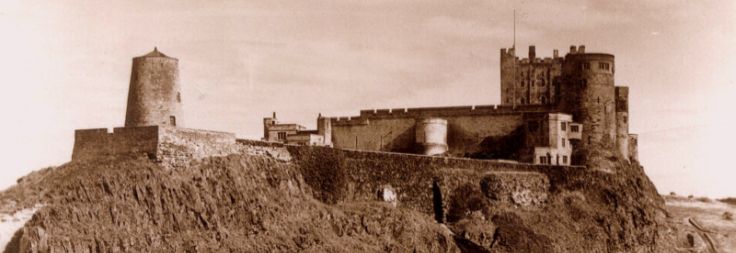

The location of Bamburgh, with its spectacular castle set on a volcanic outcrop above the sea, has assured it of a prominent place in the history of the north-east at least since its occupation by Ida, King of Bernicia, in the 6th century. It was subsequently a stronghold for the Kings of Northumbria and of England, until its military significance ended after a siege in the Wars of the Roses. The North was the centre of dwindling support for the Lancastrian faction, the castles of Bamburgh, Alnwick and Dunstanburgh being held for King Henry VI. However, as the King had stayed at the Castle on several occasions, ruling his diminished “kingdom” from Bamburgh, Edward of York ordered the Earl of Warwick to besiege Bamburgh and Dunstanburgh in 1464; both fell, to Edward’s cannon (named London, Newe-Castel and Donjon). Bamburgh Castle has been restored twice; Dunstanburgh never, remaining the dramatic ruin we know today. In the later history of Bamburgh, a popular figure associated with the area was Grace Darling, who assisted her father to rescue survivors from the shipwrecked Forfarshire in 1838.

Bamburgh on the web

Photo: Nevilley, via Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA-2.0. The history and locality of Bamburgh is described on the Bamburgh Parish website.

The Bamburgh Research Project has been pursuing archaeological and historical investigations in and around Bamburgh Castle since 1996, and these are extensively documented on their website.

More historical detail can be found on the Bamburgh Castle website.

A detailed printed history of Bamburgh (now available online) appeared in: History of Northumberland: Volume 1: The Parish of Bamburgh, by Edward Bateson. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, London: 1893. A copy of the volume is also available in Berwick Record Office.

Also online: Descriptive and historical notices of some remarkable Northumbrian, castles, churches, and antiquities … By William Sidney Gibson … Published 1848 by W. Pickering; [etc., etc.] in London . 2d ser. Dilston Hall. Visit to Bamburgh Castle. 1850.

|

Restorations of Bamburgh Castle

Nathaniel, Lord Crewe (1633-1721), whose charitable bequest funded the first restoration of Bamburgh Castle. Image reproduced with kind permission of Durham Castle.

From 1464 to the mid 1700s, Bamburgh remained largely a ruin; only the Great Tower remained intact. Henry VIII and Elizabeth ordered surveys of work needed to restore it; none was undertaken and in 1610 James 1 gave (off loaded?) the ruin to one of his supporters, Claudius Forster. The Forster family were impoverished, living in the old Manor House in the village, and it was not until one of the daughters of the family, Dorothy, married Nathaniel, Lord Crewe, that the family finances were rescued. When Lord Crewe died in 1721 – Dorothy having pre-deceased him, and leaving no issue – he left most of his fortune for the Castle to be restored and for charitable work be carried out there.

Thus started one of the most significant and dramatic periods in the Castle’s history. Under the supervision of 5 Trustees, established by Lord Crewe, from ecclesiastical institutions, the restoration of the Castle commenced. The most important Trustee by far was Dr John Sharp, eldest brother from a cultured and educated family, who inherited the Trusteeship when his father Thomas, Archdeacon of Northumberland, died in 1758. Dr Thomas had started the restoration – but only to the extent of preventing further collapse of the ruins as “they provided a landmark for fishermen at sea”. His son, who was also Archdeacon, Vicar of Hartburn with the cure of Bamburgh, and Prebendry of Durham, oversaw the restoration; he also established many local charities, chiefly Rules to assist the many shipwrecked sailors, schools for boys and girls in the Castle, a free Infirmary and Dispensary, and even a windmill to grind corn for the poor when high prices threatened starvation in the area.

The Trustees administered the Castle and Estate until the late 1800s. Slowly, their financial oversight slipped; the Charity Commissioners conducted an enquiry, and ordered the Castle be sold, and the Girls school closed. National improvements meant that many of the charitable innovations became unnecessary.

In 1894, the first Lord Armstrong bought the Castle, not to live in – his heart was always in his home at Cragside – but to convert it into a convalescent home for genteel-but-impoverished people such as schoolteachers or clergy. Sadly, he died while this second restoration was ongoing – a restoration which ultimately made the Castle we know today, but which also meant the destruction of much of the 18th century work.

William Armstrong (1810-1900)

William George Armstrong was born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1810. He attended Bishop Auckland Grammar School, and showed a youthful interest in mechanical constructions. After leaving school he was articled to a firm of solicitors, Messrs Donkin and Stable, with whom he went on to become a junior partner in 1835. In his leisure time he pursued his interest in engineering after experimenting with hydraulic machinery.

Lord William Armstrong; reproduced with kind permission of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers, London.

In 1846 he gave up the legal profession, at the age of 36, and established the engineering firm of W.G. Armstrong & Co at Elswick to manufacture new hydraulic devices. The company flourished amid the expansion of the mining and transport industries, and by 1852 it had 352 employees.

The start of the Crimean War in 1853 provided the impetus for a diversification into the manufacture of armaments, and Armstrong became a key figure in the design of field guns; in 1859 he was given the government appointment of Director of Rifled Ordnance, and he was knighted in the same year.

His various manufacturing activities made him a man of considerable wealth, and in 1863 he purchased land near Rothbury which had been a favourite place of his childhood. In 1864 he started building a house, known as Cragside, which went on to become famous for its use of hydraulic power which supplied electricity and operated the lifts in the house.

Among the many honorific positions held by Lord Armstrong were the presidencies of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, and the Institution of Civil Engineers. He also received the Albert Medal of the Society of Arts for his inventions in hydraulic machinery, and the Bessemer gold medal of the Iron and Steel Institute for his services to the steel industry. He became Baron Armstrong of Cragside in 1887. He died in 1900 and was buried in Rothbury.

Sources:

Stafford M. Linsley, ‘Armstrong, William George, Baron Armstrong (1810–1900)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006. [Accessed 3/12/2013].

William Armstrong, Magician of the North [website; accessed 1/7/2013].

On the history of the Armstrong family, see entry in Landed Families of Britain & Ireland [accessed 1/7/2019].

The 1901 Census (transcript for local areas held in Berwick Record Office) throws some light on the scale of the renovation works on Bamburgh Castle which were initiated by Lord Armstrong. For the Armstrong Cottages which were built for the workmen on the project, a few hundred yards to the south of the Castle, the Census lists the current inhabitants with, of course, their provenance and professions. 114 residents are listed for the 19 cottages, of whom 53 are working men employed in the building trade: their professions include stonemasons, joiners, plumbers, rope & pole scaffolders, blacksmiths, and plasterers. Many come from Northumberland or Scotland, but a significant proportion are from further afield: Cumberland, Westmorland, Lancashire, Durham, Yorkshire, Derbyshire – and one from the Channel Islands.

*********************

Bamburgh in the Record Office

The majority of archive resources for Bamburgh are held at the Northumberland Archives at Woodhorn. These include the extensive collection of the Lord Crewe papers which have been placed on deposit by the Lord Crewe Trustees. The content of the collection can be reviewed in the online catalogue: use the Reference Number NRO 00452 to identify the collection. Many of the entries contain detailed transcriptions from the documents, and some of them are illlustrated with images of the material. The thousands of documents – fragile old letters, handwritten account books, and maps – provide a unique glimpse into 18th century Bamburgh.

Some other sources relating to Bamburgh are held in Berwick Record Office including the following:

Bamburgh Parish Council: Minute book, 4 December 1894 – 5 September 1924 Minute book, 30 June 1925 – 9June 1947 Miscellaneous financial statements and receipt books, 1897 – 1960.

Bamburgh Parish Baptisms, 1758 – 1902.

Belford Scotch Church: Baptisms, 1776 – 1848. A register of baptisms belonging to the Protestant dissenting congregation at Belford ( Belford West Street English Presbyterian Church, later St Columba); includes Bamburgh; name index.

Warenford Presbyterian Baptisms, 1747 – 1854; 1855 – 1932. Includes some from Bamburgh.

Bamburgh Parish Marriages 1653 – 1758. 1754 – 1812; 1837 – 1875. Indexed.

Bamburgh Parish Burials, 1810 – 1902. Indexed.

Bamburgh Monumental Inscriptions A survey of the surviving grave inscriptions in Bamburgh parish churchyard, conducted in summer 1995 by Friends of Berwick and District Museum and Archives. Also includes memorials inside the church.

Bamburgh photographs. A number of aerial photographs taken pre-1974.

|

This aerial photograph of Bamburgh Castle and village was taken in 1973. Photo: Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums, Ref. TWAS: DT.TUR.7.54.

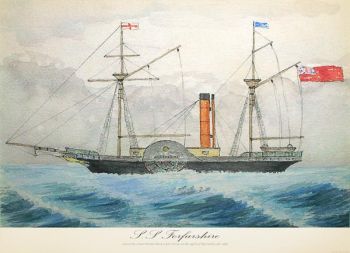

The wreck of the Forfarshire, and Grace Darling. September 1838

On Wednesday 5th September 1838 at about 6 o’clock in the evening, the steam vessel Forfarshire left Hull for Dundee, captained by John Humble. On board were 29 passengers and a crew of 23. From the start of the journey there were problems with the steam engines. However, the boat continued on its journey and by Thursday afternoon had reached Bamburgh in Northumberland. By this time the weather had become misty and the boat was under sail because the engines were not working. During the day, the boat continued to travel north and reached St Abbs Head in Berwickshire.

Early 19th century watercolour of SS Forfarshire (c.1835); author unknown. Via Wikimedia Commons.

However, by the evening a great storm arose and the captain decided to head south again to the safety of the Ferne [Farne] Islands. Between 3 and 4 am on the Friday, the boat reached the Ferne Islands and the captain thought they were safe but, because of the mist, he had mistaken the Outer Ferne lighthouse for the Inner Ferne one. Therefore, instead of being near the shore and Bamburgh, the boat was on the treacherous rocks between the two lighthouses. The boat struck a rock known as the “Great Hercules” and immediately started to sink. Some of the crew abandoned the ship in a lifeboat, not thinking about the passengers and their fate, and they were picked up at North Shields.

The rest of the passengers and crew were forced to cling to the wreckage and wait for help. On realising that the ship had struck the rocks in the storm, William Darling and his daughter Grace, who were the only people on the Outer Lighthouse that night, launched their boat and tried to rescue the survivors, some of whom had now reached one of the Farne’s rocky outcrops. This newspaper article which appeared in the Berwick Advertiser described their deed as follows:

“This was the situation of the survivors till daylight, when the ebbing of the tide enabled them to quit their lurking places and land on the rock.

“Here they remained for some time, when their situation was descried by the keeper of the outer lighthouse, whose only companion at this dreary place was his daughter, a girl about 19 years of age. To resist attempting to alleviate distress is with some persons utterly impossible; such seems to be the character of William Darling and his daughter Grace.

“The conduct of these two individuals on this occasion is worthy of the highest praise, and we feel assured will not be allowed to pass unrewarded. Although the sea was raging with a fury which might have daunted even a bold spirit, this man and his brave daughter, disdaining all selfish considerations for their own safety, no sooner perceived the perilous situation in which some of their fellow creatures were placed, than they launched their boat, without hesitation into the foaming element, and pulled vigorously to their relief, a distance of “300 yards; and having returned with them all safe to his dwelling, everything that it afforded was willingly placed at their disposal. Such behaviour affords a pleasing contrast to that displayed by the crew of the vessel, who, had they possessed a spark of that generosity and courage which dictated the conduct of Darling and his daughter, would have lingered about the wreck, and in this way, they might have been instrumental in saving their companions from a watery grave.”

The surviving passengers and crew were later taken to Bamburgh. On Tuesday 11th September an inquest was held in Bamburgh into the incident. The Coroner and the Jury heard evidence as to how the four people whose bodies had been found had died, and they recorded a verdict of “accidental death”.

This newspaper article, under the title “Loss of the Forfarshire steam vessel, and thirty five lives”, gives a very full account of the wreck and the inquest, and the courage displayed by Grace Darling and her father in rescuing the survivors.

Berwick Advertiser 15th September 1838 p.4.

The death of Grace Darling (1815–42)

An article in the Berwick Advertiser (29th October 1842, p.4) recorded the death of Grace Horsley Darling, aged almost 26, on 20th October 1842 in Bamburgh, and included the following detail:

“Up until April last she had been blessed with excellent health; but in the course of that month she caught a cold which settled down upon her lungs. In June she came to Bamburgh, where she was sedulously waited upon by her sister, and had the medical aid of Mr Fender, the resident doctor. She subsequently went to Wooler for a change of air, and afterwards to Alnwick, where she was repeatedly visited by the Duchess of Northumberland, who requested that nothing should be wanting that might alleviate her suffering and procure her recovery. All hope having vanished, she returned to Bamburgh, to be near her friends.

“…The circumstances which brought Grace Darling prominently into notice is still fresh in the public recollection, and her memory will be long cherished not only for the daring achievement in which she bore so distinguished a part, but for the modest and unaffected simplicity with which she received the praises that event called forth.”

Grace was buried in Bamburgh Parish Churchyard in which there is now a large monument erected to her memory.

The Grace Darling Website tells the story of her family, her life and her legend.

The RNLI’s Grace Darling Museum illustrates her story with artefacts and documents.

*********************

The banner image at the top of this page is taken from a postcard of Bamburgh Castle (early 20th century) which is held in Berwick Record Office (BRO 0515/25).